Rajat

Polluting The Global Namespace Is A Crime Worthy Of Death

05 SEP 2019 - 4 MINS

I recently came across an error very similar to this one in a colleagues’ code when he was using pyspark for an exploratory data analysis - can you guess what caused it?

>>> cat eda.py

from helper import *

# Some code goes here

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Some more code goes here

print(sum([1, 2, 3]))

>>>

>>>

>>> python eda.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 7, in <module>

File "/Users/rajatrasal/anaconda3/envs/spark/lib/python3.7/site-packages/

pyspark/sql/functions.py", line 44, in _

jc = getattr(sc._jvm.functions, name)(col._jc if isinstance(col, Column) else col)

AttributeError: 'NoneType' object has no attribute '_jvm'

Why am I getting errors to do with the JVM when I’m using Python’s inbuilt sum function?!?!?! 😰😓

Before we go any further, I want to make it completely clear that I would never write code like this! There are so many issues associated with import *-like statements. They pollute the global namespace and make code very hard to follow, resulting in many unusual errors that, with very little extra effort, are completely avoidable.

After coming across this error, I became quite interested in seeing how other programming language compilers and interpreters handle issues with global namespace pollution. Python was greatly influenced by Java1 and C++2. By examining how these languages handle errors with namespace pollution, I thought I would get a better understanding of Python’s core design philosophy.

Java

In Java, the import keyword is used to indicated packages and classes where classes/types can be used from. There are 2 kinds of imports:

- Single type imports, e.g.

import java.util.List, allows us to use a class/type within a file without having to use its fully qualified class name each time. - On-demand imports, e.g.

import java.util.*, indicates that any class/type within the package could be used within the code without being fully qualified.3

These types of imports (and more) are also found in Python and have the same behaviours.4

Packages and imports (as well as access controls) in Java allow the developer to split up a large codebase to prevent identifier names clashing. This also helps to better encapsulate different sections of the codebase from each other. However, careless use of on-demand imports can result in the kind of confusing and unnecesary import errors we want to avoid. So it’s best not to use this style of imports altogether, and use fully qualified classnames if required. Google’s code style explicity prohibits wildcard imports for this reason.

>>> cat Test.java

import java.util.*;

import java.awt.*;

public class Test {

public static void main(String[] args) {

List x = new ArrayList();

}

}

>>>

>>>

>>> javac Test.java

Test.java:6: error: reference to List is ambiguous

List x = new ArrayList();

^

both interface java.util.List in java.util and class java.awt.List

in java.awt match

1 error

The Java compiler handles clashing identifiers by throwing an error and stopping the compilation of the file. It seems as if all classes/types found by looking in the packages specified by the import statements at the top of the file are appended to a global symbol tables by the compiler, then during the semantic analysis stage of the compilation, an error is thrown when the conflicting class names are detected. As Java is a compiled language, this bug will luckily never make it to the runtime stage.

Even if the on-demand imports don’t result in a clash, as the ones above did, they may still increase compilation times given that the semantic analyser may have to search through large package structures, especially if the packages have not been converted to jars 5. Although this may not cause a significant time delay for the (re)deployment of an application or result in any latency at runtime, it may slow down CI/CD pipelines and spin up times for Docker containers when testing as your project size gets larger. This could be a real nuisance during development.

One of the most annoying situations I can imagine is when an external package you are on-demand importing gets updated. So if external_animal_package creators make their own Dog class one fine day, the code below will suddenly fail, and I’ll have to go through the effort of carefully refactoring what, at this stage, might have become a very large java file6.

import animals.*;

import external_animals_package.*;

public class Test {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Dog x = new Dog();

}

}

C++

C++ introduces the concept of namespaces as a programming langauge construct.

A namespace is a mechanism for expressing logical grouping. That is, if some declarations logically belong together according to some criteria, they can be put in a common namespace to express this fact.

Java implicity allows for namespacing through packages. The details of the differences between each are beyond the scope of this article but are explained quite nicely in these stack overflow posts 1 2.

We can see that the key purpose of namespaces in software engineering isto allow developers to assign a scope to identifiers (i.e. variables, functions, classes etc.) and prevent name collisions as a project becomes larger and requires better structure.

Yet even with the introduction of namespaces a lazy programmer can end up polluting the global namespace through the using directive. This causes the same name clashing issues we would have had without namespaces. This is especially problematic with C++, whose standard library has become quite bloated over the past few versions. Consider the following snippet of code which compiles just fine up until C++14 but fails in C++17 - this minor issue could result in decades worth of code having to be refactored!

>>> cat test_bytes.cpp

#include <string>

using namespace std;

class byte {};

int main() {

byte test_byte;

return 0;

}

>>>

>>>

>>> g++ -std=c++14 test_bytes.cpp -o test_bytes.o

>>>

>>>

>>> g++ -std=c++17 test_bytes.cpp -o test_bytes.o

test_bytes.cpp:8:3: error: reference to 'byte' is ambiguous

byte test_byte;

^

test_bytes.cpp:5:7: note: candidate found by name lookup is 'byte'

class byte {};

^

/Library/Developer/CommandLineTools/usr/include/c++/v1/cstddef:65:12:

note: candidate found by name lookup is 'std::byte'

enum class byte : unsigned char {};

^

1 error generated.

Once again Google’s style guide prohibits the using-directive to make all names from a namespace available.

A better way to separate the std::byte from our own definition of byte would be to:

- use fully qualified definition imports (seen below),

- make use of anonymous namespaces (seen below) or, if you are developing a library,

- wrapping the entire source file in a namespace.

#include <string>

namespace {

class byte {};

void create_byte();

}

namespace create_bytes {

void create_byte() {

byte test_byte;

}

}

int main() {

using std::byte;

std::byte test_std_byte;

create_bytes::create_byte();

return 0;

}

The worst case scenario I can think of here is using an entire namespace from a header file such that all the identifiers within the namespace end up as part of a published API.

Back to the problem - Python

Unlike Java and C++, name clashes in Python cannot be resolved until runtime since Python is an interpreter language.

Namespaces

Python has its own unique take on namespacing and scope resolution.

A namespace is a mapping from (identifier) names to objects. Most namespaces are currently implemented as Python dictionaries...

Moreover, given that the keys of a dictionary form a set, i.e. keys must be unique, this ensures that all identifiers in a namespace are unique (which I think is quite neat).

Examples of namespaces in Python would be the set of builtin names __builtins__, containing all of Python’s out-of-the-box functions such as sum() or list(), the global names, such as global identifiers or imports at the top of a Python file, and local names which we find within a code block, such as a for loop variable7 or the local variables of a function8. All the identifiers which are found after executing an import statement at the top of a Python file end up in the global namespace. Consider the example given at the beginning of this article:

# Bash

>>> cat helper.py # prints contents of helper.py

from pyspark.sql.functions import *

# Some code goes here

# End of file

>>>

>>>

>>> python # Starting Python shell

# Python Shell

>>> globals().keys() # names of all global identifiers

dict_keys(['__name__', '__doc__', '__package__', '__loader__', '__spec__',

'__annotations__', '__builtins__'])

>>>

>>>

>>> from helper import *

>>> globals().keys()

dict_keys(['__name__', '__doc__', '__package__', '__loader__', '__spec__',

'__annotations__', '__builtins__', 'PandasUDFType', 'abs', 'acos',

'add_months', 'approxCountDistinct', 'approx_count_distinct', 'array',

'array_contains', 'array_distinct', 'array_except', 'array_intersect',

'array_join', 'array_max', 'array_min', 'array_position',

...

...

>>>

>>> 'sum' in globals().keys()

True

The import * statement in helper.py has resulted in all the functions from pyspark.sql.functions being added to the global namespace. Pyspark also seems to have its own sum function, which is also added to the global namespace. This is akin to the behaviour expected when using an entire namespace in a header file and then including that header file in a .cpp file, as I suggested at the end of the C++ section9.

Scope

In the global namespace, we can also find the __builtin__ namespace dictionary and any local identifiers. This structure resembles the symbol table created during the parsing of Java or C++ code. In all three languages, this enables us to create a scoping mechanism.

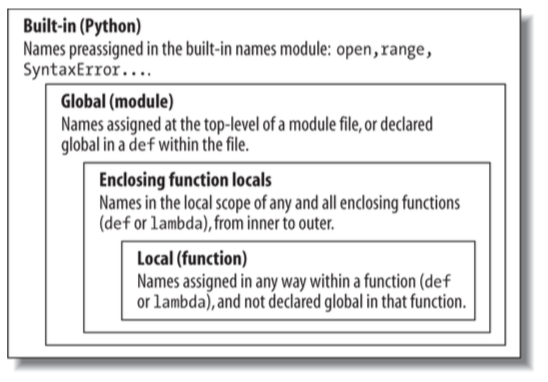

The LEGB rule describes the order in which Python goes about scope resolution, as described in Learning Python:

- Local scope is first search for names, which contains all keys within the

locals()dict. - Enclosing scope is then searched, i.e. when a function is defined within another function.

- Global scope containing all keys from the

globals()namespace. - Finally the Builtin scope, with identifiers from

__builtins__.

Hence why pyspark’s sum function is called instead of the inbuilt one; Python finds the global pyspark.sql.functions.sum before it finds the builtin one and goes with the first identifier it finds.

If we manually delete pyspark’s sum from the globals() dictionary, we get the expected behaviour again. But this is not the solution to our problem.

# Python Shell

>>> from pyspark.sql.functions import *

>>>

>>> del globals()['sum']

>>>

>>> sum([1, 2, 3])

6

Solution to our problem?

So this problem seems to be a combination of 3 things:

- Python’s unique scoping mechanism doing its job.

- The fact that Spark’s Scala interface has been kept exactly the same in Python without much thought that such a clash might occur.

- The use of

import *making the error much harder to debug.

We could solve this by changing the line from pyspark.sql.function import * to from pyspark.sql.function import sum as _sum. On importing a file in Python, that file is executed and all globally available identifiers are added to the global namespace. However, any identifier names which are prefixed with at least one underscore cannot be accessed from another file using import * and WILL NOT POLLUTE THE GLOBAL NAMESPACE. These functions can only be accessed by using a fully qualified import. So when there is a possibility of a clash or you would like certain helper methods to remain hidden, unless explicity asked for, they should be marked with an underscore prefix. This defensive naming strategy also protects your entire codebase from coder’s who might try to import * from various files.

>>> cat helper.py # prints contents of helper.py

from pyspark.sql.functions import sum as _sum

# Some code goes here

# End of file

>>>

>>>

>>> python # Starting Python shell

# Python Shell

>>> from helper import *

>>>

>>> '_sum' in globals().keys()

False

>>>

>>> import helper

>>> dir(helper)

['__builtins__', '__cached__', '__doc__', '__file__', '__loader__',

'__name__', '__package__', '__spec__', '_sum']

>>>

>>> '_sum' in dir(helper)

True

>>>

>>> from helper import _sum

>>> _sum

<function _create_function.<locals>._ at 0x114ff4320>

>>> sum

<built-in function sum>

TL;DR?

Just use fully qualified explicit imports! Please.

References

- Phases of Compiler Design - Tutorialspoint

- Java Compilation overview OpenJDK

- Java in a Nutshell by Benjamin J. Evans & David Flanagan - Importing Types page 90 - 95

- The C++ programming language by Bjarne Stroustrup - Chapter 8 Namespaces and Exceptions

- Learning Python 5th Edition by Mark Lutz - Chapter 17: Scope

- Scopes and Namespaces in Python - Python Documentation

- Role of Underscore(_) in Python from the DataCamp blog

-

Obvious aspects of Python syntax and style, and the syntax of many other languages’, is influenced by Java. https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0318/ ↩

-

Python’s class mechanism is greatly influenced by cpp: https://docs.python.org/3/tutorial/classes.html ↩

-

The Java interpeter (i.e.

javacommand line tool) is responsible for translating the .class file containing the Java bytecode to machine dependent object code which can be run. ↩ -

Read this article for a better explanation of how the Java compiler goes about finding definitions for classes which have been used within a .java file. It is beyond the scope of this article but may help bridge the gaps in my part explanation. ↩

-

Of course all large Java projects should be split up into microservices, with each being packaged into a jar, but seeing as we are looking at bad coding practices I thought the case of not converting packages to jars would be appropriate to mention. ↩

-

Intellij, or even clever usage of the sed bash command, might make this process easier, but its still a real pain having to go through it. Just use explicit single type imports to begin with. Please! ↩

-

Unlike many other programming languages, for loop iteration variables are ‘forgotten’ once we leave the for loop scope. When entering the for loop, the iteration variable would be added to the

locals()namespace dict. When leaving this block,delwould be called on the key associated with the for loop variable which was previously added to thelocals()dict. ↩ -

Objects also have their own namespace created by name mangling in Python. This is the reason why identifiers in Python can never be completely private - at best can only be marked as private. ↩

-

Although the behaviours are similar but the actual implementation varies greatly.

Includeis a compiler directive in C++ and is executed by the preprocessor prior to assembly code generation. It essentially links up all the file which are to be included into a single large file. Python works slightly differently in that every module which is imported is actually executed, which in turn builds up the global namespace by adding identifiers to theglobals()dict. ↩

Did you enjoy this post?

If you did, check out my Github repo - I've got some cool projects on there. I also post these articles on Medium, so you could get notifications when they get posted if you download the Medium app and subscribe to my feed. Alternatively you could even subscribe to my feed on this site and get notified by my updates here. Add me on social media too. It's quite possible that you didn't like this article. I'd love some feedback!